Political reforms must take place, and Bashar Al Assad, far from the perfect figure his supporters see, is still the only leader that can lead Syria to free elections. Moderate, secular opposition must reclaim the revolution from the militants and those who are genuinely concerned about stability and democratic reforms in Syria should stop supporting “the opposition” and instead recognize and empower moderates from both the regime’s side and the opposition’s.Some highlights from the article (which is definitely worth reading in full)

-In his eleven years in office, Assad's lowest marks come on fighting corruption. There is a definite perception in Syria that "the rich got richer, while the poor got poorer." As the upper class benefited, hundreds of thousands of Syrians moved from the drought-stricken rural areas, where they were receiving little government assistance, to the outskirts of major cities like Damascus and Aleppo, a process that the historian Gabriel Kolko has termed "forced urbanization." However, the Western Media claims that Assad and his family have looted the Syrian treasury to the tune of billions of dollars are also false. When Swiss banks froze Syrian accounts last December following EU sanctions, they seized only $53 million, which was spread over 54 top officials and 12 companies. Syria also has virtually no national debt, despite having a large military budget and a relatively successful welfare system which provides free education and healthcare for the states 23 million citizens. If Assad and co were stealing the national wealth, it had to come from somewhere, and it is hard to see where that is. Summing up the personal habits of the Syrian president, Otrakji writes:

President Bashar himself enjoys computers and expensive professional digital cameras. But he also lives in his father’s old apartment after renovating it and furnishing it with modern furniture and art. He drives luxury cars donated as gifts to the Presidential Palace by fellow Arab rulers of GCC countries, but never drove exotic cars and refused offers of exotic cars as gifts from his friends in Qatar, Kuwait or the UAE. When he was younger, and when his older brother was into Italian exotic cars, Bashar drove a small Peugeot sedan. He enjoys playing tennis or cycling with his family or his old friends for hours outdoors. His wife, the first lady, is well known for her expensive taste in European fashion brands but she does not wear expensive jewelry and instead wears mostly fashion jewelry. While the President likes to stay close to his old friends, the first lady tends to favor the friendship of members of leading business families from Syria and Lebanon. She is a hard worker and a perfectionist who was clearly recognized as the Arab world’s most successful first lady.

-Assad also receives low marks for his political appointments, most notably Iyad Ghazal as Governor of Homs. Gazal is a close friend of the President, and seemingly became rich out of nowhere (see corruption above). He is just one example of Assad's trend of appointing, "Prime Ministers, Ministers, governors and senior officials that were too often corrupt, inefficient, unqualified and, in general, undistinguished in any way."

-The popular opinion of Assad's personality, however, is high, both in Syria and the region. In 2009, he won a CNN Arabic poll for the region's most popular leader, and in 2010 finished second to Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan. He (as opposed to his government) is also not viewed as sectarian, despite his Alawite background, and has the support "of all minorities and a majority of Sunnis" as written by Jihad el-Khazen, the former editor of the major Arab newspapers Alhayat and Asharq Alawsat.

-Assad also scores popularity points for his perceived resistance to Western and Israeli hegemony in the region, a fact that for many Syrians transcends religious, geographic, and economic lines. Many of the earliest U.S. calls in 2011 for overthrowing Assad came from the far right and neoconservative movement, such as Elliot Abrams, Joe Lieberman, and Donald Rumsfeld. Otrakji sums up the situation well, writing:

While the coalition opposed to Assad successfully promoted it’s role as a champion of individual political freedom and dignity, Assad’s supporters’ reaction was: “great, but never at the expense of our national freedom and dignity”. This is a key element that western media fail to understand about the psychology of the Syrian people. Many Syrians are more preoccupied with protecting their country’s national interests rather than their own right to challenge President Assad at the 2014 Presidential elections. You will not convince them to sacrifice their national dignity in favor of promises by a highly energetic coalition of all the Gulf Arabs, Turkey, and western countries that often attempted to control Syria’s decisions, suppress Syria’s aspirations, or simply weaken Syria’s role in the region so that they can enjoy more influence.-In his response to the crisis in 2011. Assad obviously saw his popularity decrease. However, this was not in a zero-sum fashion, as opposition leaders like the SNC's Burhan Ghalioun also lost popularity as the year progressed and a stalemate began to take hold between violent government forces and violent protesters. In an opinion that is sure to be disputed, Otrakji writes:

Despite Assad’s declining popularity he continues to be considerably more popular than any specific opposition figure. To many Syrians who are not by now irrevocably opposed to him, Assad is the only experienced leader who can run their country, regardless of their satisfaction with his handling of the recent crisis.-On the topic of various demonstration sizes, Otrakji concludes that both pro and anti government rallies have been overestimated in size. He estimates that opposition demonstrations in Hama and Deir Ezzore had around 30,000 participants each (far less than the 500,000 participants alleged by some media), while obviously many Syrians did not attend these protests out of fear. He estimates that pro government rallies consisted cumulatively of one million people, who attended out of their free will, and not through methods of state coercion.

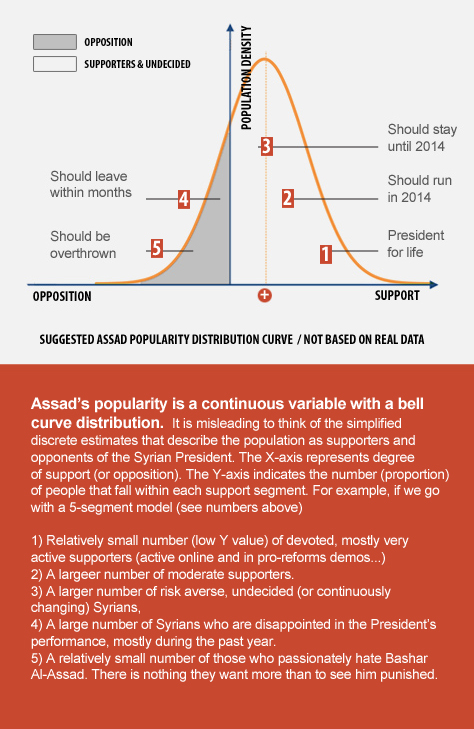

Before the Arab Spring made it to Syria, the assumption by those in the regime’s camp was that Syria will be spared because the President and the regime are too popular to be subjected to a rebellion. After protests started, western and Arab media flipped to the opposite assumption … that the Syrian President’s support is surely comparable to his Tunisian and Egyptian counterparts’ marginal popularity. Both assumptions proved to be wrong. There is enough support, opposition, and indifference to make all potential outcomes of the crisis possible.Otrakji gives a visual representation of what he believes the scope of Assad's popularity to be. As he stresses, this is a visual aid of his estimations, and not based on any actual data.

-Otrakji also writes of the three "red lines" for Assad that all political negotiations will hinge on. The first is to protest the legacy and reputation of his, and his fathers, rule. The second is to manage the reform process to make sure that the new Syria protects ethnic minorities, and keeps its secular nature. The latter will be a major challenge, as the Muslim Brotherhood has been the most vocal and well represented members of the international opposition (The SNC). The third redline is Syria's independent foreign policy, as opposed to "moderate" Arab states like the Saudi's and Egypt who frequently side with the United States and Israel.

No comments:

Post a Comment